The Legacy of the Braceros

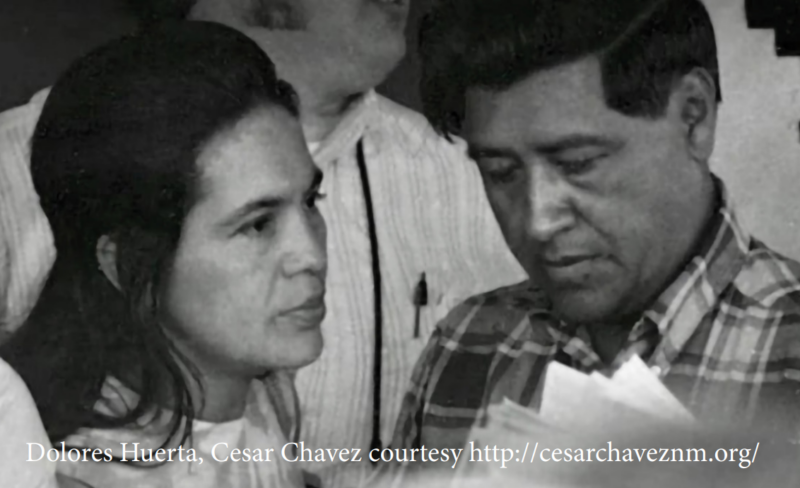

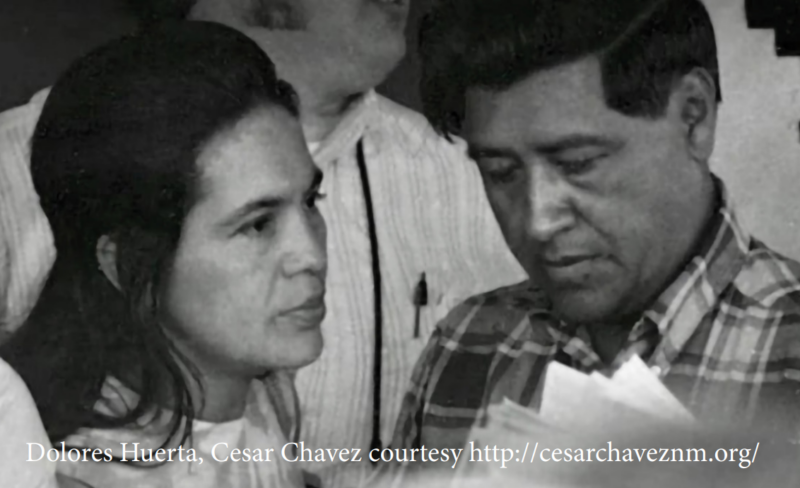

Every spring, we commemorate activists Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta for their remarkable contributions to the Farm Labor Movement by fighting for fair labor practices and civil rights.

Historically Speaking: The legacy of the Braceros

Chavez passed away in 1993, but Huerta, now 93, continues her advocacy work with the same passion as she had in the 1960s. This is fortunate because the need for advocacy persists.

Today, as much as 50 percent of all farmworkers in the U.S. work in California, and 75 percent of California’s farmworkers are undocumented. The lion’s share of our migrant farm workers are natives of Mexico. Their ongoing struggle is a stark reminder of our historic failure to do right by the people whose labor in our fields still puts food on our tables today.

Between 1910 and 1929, the Mexican Revolution created unrest, poverty and displacement in that country. Meanwhile, Europe was caught up in World War I and European migration to the U.S. declined, creating demand for farm and railroad labor here at home. Immigrants from Mexico filled the void as temporary guest workers during the first Bracero Program (“Bracero” comes from the Spanish word brazo, or arm, referring to manual labor).

By the early 1940s, America had become embroiled in World War II and American farm workers left their farms to serve in the military or fill new industrial jobs to support the war effort. The U.S. government responded to the bombing of Pearl Harbor by forcing Japanese American citizens, many of them farmers, into internment camps. To keep our agricultural economy running we turned once again to Mexico.

In 1942, U.S. and Mexican government leaders negotiated the Mexican Farm Labor Agreement, followed by the Migrant Labor Agreement (enacted into Public Law 78 in 1951). The Bracero Program was reinstated and Mexican men were once again recruited as temporary guest workers to harvest U.S. crops. Agreement terms included specific provisions for fair wages, housing, food, transportation and health care. The Mexican government’s hope was that workers would gain new skills and earn wages in America that they would bring back to Mexico and help stimulate their economy.

With so many Mexicans seeking employment, jobs were highly competitive. Farm bosses prioritized young workers, the ones with calluses on their hands. There were long waits at the border before men were admitted to processing centers, where they were fingerprinted, and their belongings searched for weapons and marijuana. They had to remove their clothes and were subjected to humiliating physical exams after which they were sprayed with DDT. If selected, they were bused to various locations, primarily to harvest crops, with no choice as to where they were sent or who they worked for.

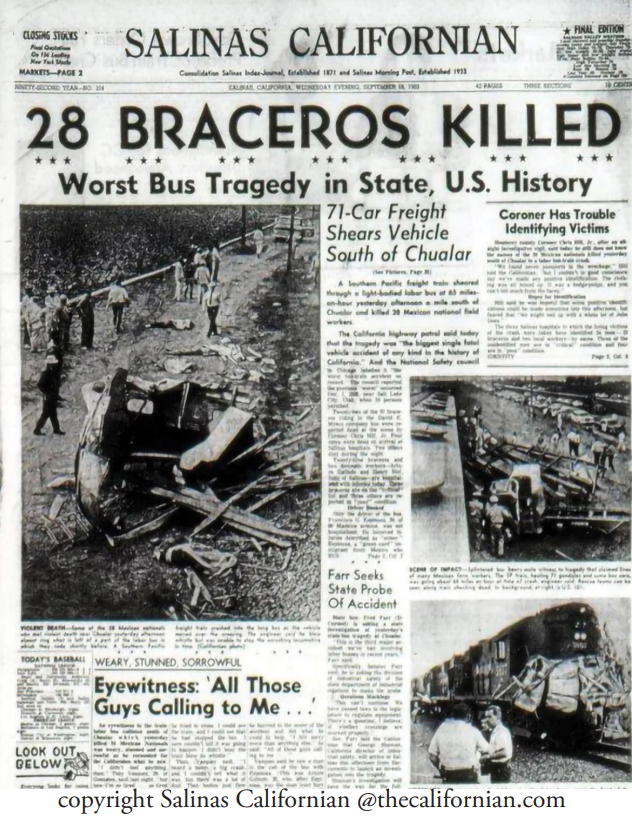

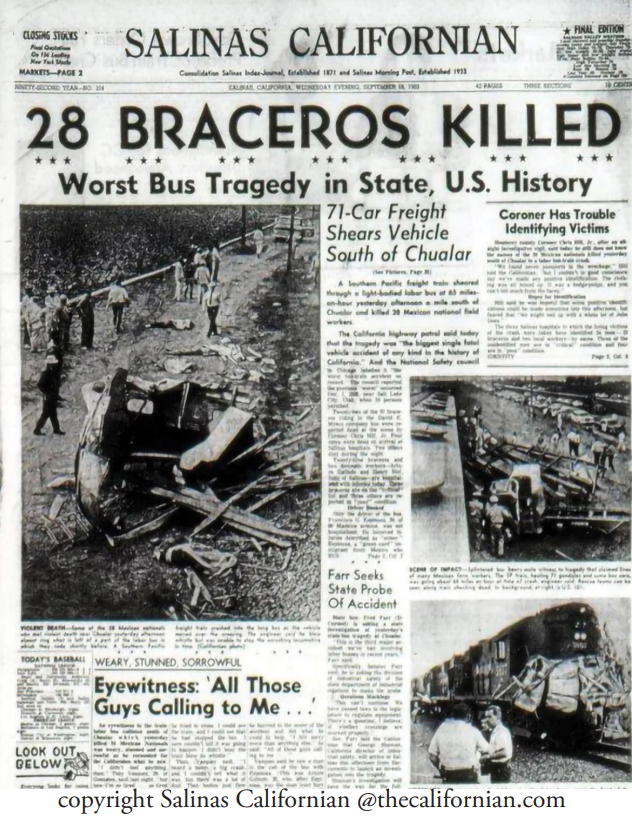

The Bracero Program was beset by violations of the agreed upon terms. Worker protections were often ignored. Laborers regularly worked unpaid overtime. “Stoop labor” was a common practice whereby workers were supplied with hoes with very short handles. These hoes made it easier for them to work in tight crop rows and were cheaper to supply, but they forced workers to stoop low and resulted in chronic back injuries.

Banuelos explained, “Some farm owners treated their workers well and supported them in getting green cards so they could extend their stay, advance their skills and earn higher wages. But at times, farm owners and U.S. authorities turned a blind eye to discrimination, unsafe working conditions and withholding of wages. When confronted with the injustices, their common refrain was, ‘What’s the big deal? They’re used to living like this.’”

“The borders were fluid in those days,” Banuelos said. “Border patrols handled things differently than they do today. Everyone knew labor was needed. Farm owners who did get caught just shrugged it off and paid the fines. They chalked it up to the cost of doing business.”

More than four million natives of Mexico migrated to America during the Bracero Program to work on farms and railroads, some legally, others illegally.

The rise of the United Farm Workers, led most famously by Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta, as well as others, organized farm labor workers and pressured U.S. government agencies for labor and civil rights reforms. This and other factors, such as mechanization, led to the Bracero Program’s termination in 1964.

Lee G. Williams, a U.S. Labor Department executive, ran the Bracero Program from 1959 until 1964. Years later, he reflected on the program in an interview with the Dallas Morning News, calling it “legalized slavery” and adding, “I pray they don’t reinstate this type of program…nothing but a way for big corporate farms to get a cheap labor supply from Mexico under government sponsorship. The whole thing was supposed to be humanistic, but it was far short of what it should have been.”

Banuelos remembers picking crops as a young boy in Stockton, back in the days when the new school year didn’t start until the harvest was in.

Banuelos moved to Morgan Hill in 1988. He has had many positive experiences volunteering with other community members to help migrant farm workers in the community.

“Many are here on their own. They work multiple jobs trying to make ends meet and send money home,” Banuelos said. “They write their names and phone numbers on their hands or on their pants, ‘in case anything were to happen,’ so someone could call their family back home. As undocumented workers they are vulnerable. Our legal system has grown complicated and it’s backlogged. For many people, time runs out while they’re waiting for help. And they continue to do the majority of the farm work that supports Santa Clara County’s economy.”

California is the world’s fifth largest supplier of food, cotton fiber and other agricultural commodities. We’re first in the nation for agricultural cash receipts. Our agricultural exports top $25 billion annually, and our farmers produce over one-third of the vegetables and two-thirds of the fruits and nuts in the U.S.

For more than a century we’ve benefited greatly from the labor of people who are largely invisible to us and vulnerable to the flaws in our labor, immigration and judicial systems. Yes, awareness is growing, policies are changing, communities are taking action, but we still have a long way to go.

Robin Shepherd contributes this column on behalf of the Morgan Hill Historical Society. Mario Banuelos is President-Elect of Morgan Hill Rotary Club, a board member of the Morgan Hill Community Foundation, and this year’s recipient of the Leadership Excellence (LEAD) award from Leadership Morgan Hill.

Sources:

• Bracero Program History, Immigrationhistory.org

• Bracero Workers in California 1960 – Harvey Richards Media Archive

• CA Dept Of Ed/History Social Science Framework, californiahss.org/BraceroProgram.html

• Calisphere, calisphere.org/exhibitions/36/the-bracero-program/

• Forgotten Voices: Story of the Bracero Program, youtube.com/watch?v=AL5d9CWV0Xg

• Harvest of Loneliness, https://bit.ly/40RrqMf.

• Stoop Labor, imdb.com/title/tt1658805/

• Harvest of Shame 1960, youtube.com/watch?v=yJTVF_dya7E

• Library of Congress, guides.loc.gov/latinx-civil-rights/bracero-program

• US Dept of Labor, https://bit.ly/3E5spym